If you’re like me, your enchantment with orchids was sparked by an encounter with a tropical/subtropical one in full floriferous glory. That’s the way it usually happens, this onset of our benign addiction and dedication to what are surely the world’s most exquisite flowers and the plants that bear them.

Quite simply, orchids are amazing. Their flowers frequently come in a riot of dazzling colours and hues arranged in intricate patterns, and in shapes so exotic and intriguing as to both fascinate and nearly defy description. Orchids are also master manipulators, often sweetly seducing their pollinators with rich perfumes and nectars, or with visual trickery designed to coax suitors into thinking their flowers are female insects, or with devices that otherwise force their pollinators to collect and carry their pollen masses to the next flower.

Stanhopea wardii’s exotic flowers intoxicate visiting male euglossine bees with their heady, seductive fragrance while also forcing them to exit their flowers in such as way as to fix pollen onto their backs for transfer to the next flower they visit. – Photo Credit: Tom Shields

Orchids are equally masters of living where few other things can: tree limbs, rocky outcrops, cliffs above waterfalls, beaches, and typically in our northern climes the edges of fens, bogs, marshes, swamps, on mountain slopes, or in wet meadows or shady forest glens. Their uncanny ability to thrive in such nutrient-poor, borderline habitats makes their needs very specific, and therefore their continuing existence vulnerable.

Our native Grass Pinks (Calopogon tuberosus) like life on the edges of wetlands. Bees are attracted to the yellow, stamen-like bristles on their lips, which they mistake for tasty pollen. Once they land, however, a hinge in the lip drops them onto the column below where the real pollen is affixed to their backs to carry to the next flower that they visit! –Photo Credit: Kevin Tipson

For example, their roots need a growing medium that provides air as much as moisture and just the right acidity or alkalinity for them to thrive. The light that reaches them must not be too strong or weak, the temperature neither too cold or hot, the humidity high enough and the air movement adequate to both prevent desiccation and keep pests at bay, and so on.

Their very specific pollinators must also visit at just the right time to let them grow their tiny seed for future generations, and that wind-blown seed must then land exactly where symbiotic microfungi will help them grow their first leaves and roots. Even thereafter, growth will be so slow that it may take a decade or more for them to flower. Being an orchid is risky business!

Put it all together and it’s easy to see why orchids are seriously threatened by human activities such as logging, mining, agriculture, property development, road construction, poaching, and greenhouse gas emissions. Destroy their sensitive habitats, or only pollinators via pesticides, or warm the Earth too much too fast and they’re gone. Unlike us, they can’t pack up and move.

The stark message is this: orchid species worldwide need our help. Even if you only grow hybrids, those hybrids owe their existence to the diversity of species in the wild, and those species are everywhere vulnerable or threatened in whatever country you wish to research, including right here in Canada. Several that once were much more numerous are now uncommon or rare, while others have been pushed to the brink of extinction, and some even over the edge.

Due to habitat destruction, the beautiful Small White Lady’s Slipper, Cypripedium candidum, is now very rare and highly endangered both in Canada and in the United States. It is just one of 17 of Canada’s 74 native species threatened with extinction. -Photo Credit: Kevin Tipson

It is an unsettling and disturbing thought, and yet there are things you and your society can and should do. First, make members aware of the problem. This is easy enough. Just stand up at regular meetings and make the point that wild orchids need our help, and do it more than once.

Second, decide on a course of action. A good way to start is with a discussion group or seminar that leads like-minded members to strike a committee to research native orchids in your area or in “hot spots” around the world to discover the problems they face and why, and what can be done. Encourage people to participate, and schedule regular meetings that will equally serve as social occasions as well as forward the goals of conservation.

Conservation enthusiasts discover a large colony of not-quite-yet-blooming Showy Lady’s Slippers (Cypripedium reginae) on a native orchid discovery walk. Several other species were also found and recorded, some unexpected. What could a committee from your society uncover? -Photo Credit: Tom Shields

Third, set goals and assign duties. What’s achievable, and who will do what? It is amazing what hidden strengths and talents people reveal when they are given responsibility and a chance to shine. Chances are excellent that you will delight yourselves and make your society proud. Consider teaming up with members of a nearby society as well; strength in numbers works wonders!

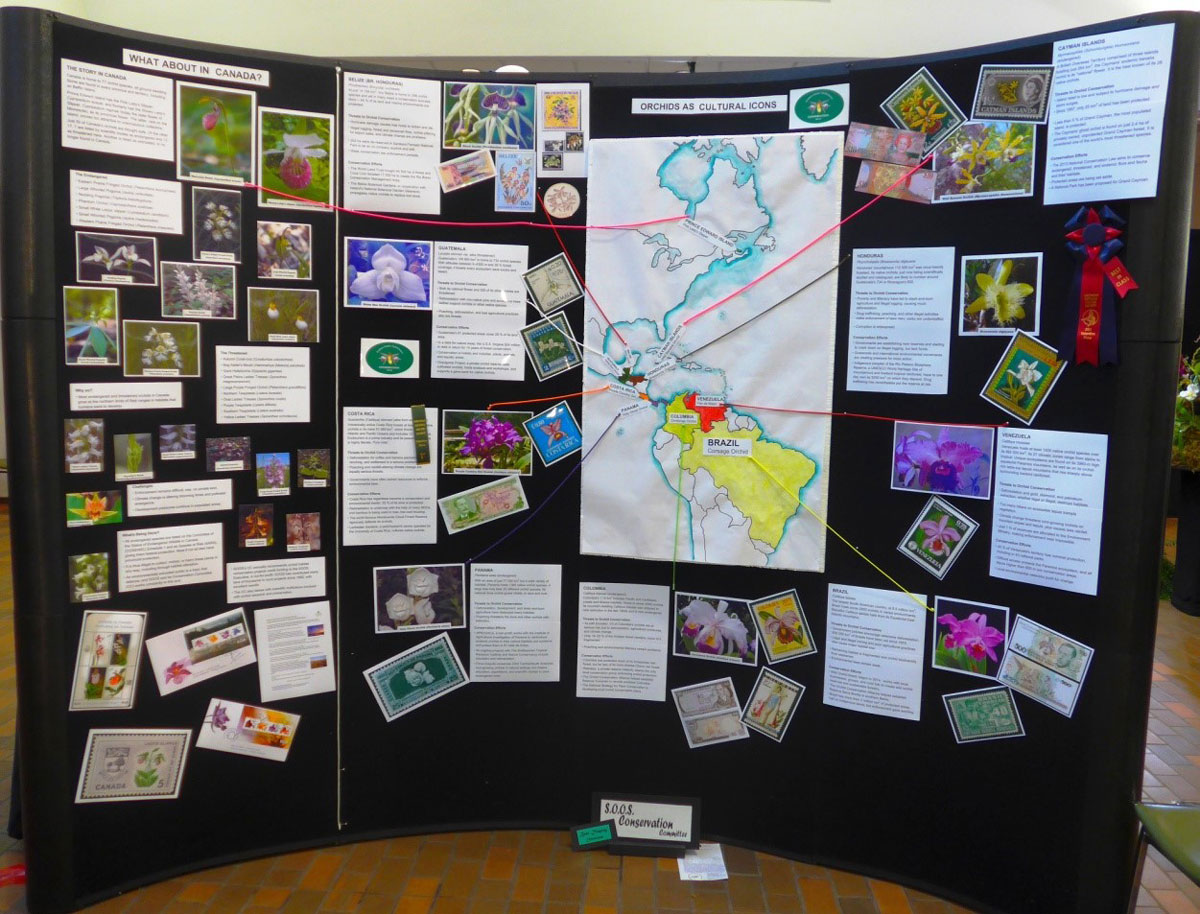

Fourth, get the message out there, educate the public at large, and build liaisons. A conservation display at your annual show illustrating what your group has accomplished and is working towards is a great way to start building awareness and make added contacts, but it needn’t stop there.

This recent conservation-themed display at a Canadian orchid show won 1st place, best in Class, and a rare Educational Exhibit award from the American Orchid Society. -Photo Credit: Tara Seucharan

Your work will prove both fun and personally rewarding, plus demonstrate to others in the serious business of conservation and habitat preservation as well as to prospective new members that your society’s roots run deeper than those of just another pretty flower club; i.e., one that is actively working to make a difference. Your work will elevate your society’s prestige and lead to greater recognition and likely larger membership. We hold orchids in trust, and life without them is something I’m sure none of us or our children’s children ever want to imagine.

_Tom Shields

Tom Shields is the COC’s Conservation Officer.